statue gardens of history

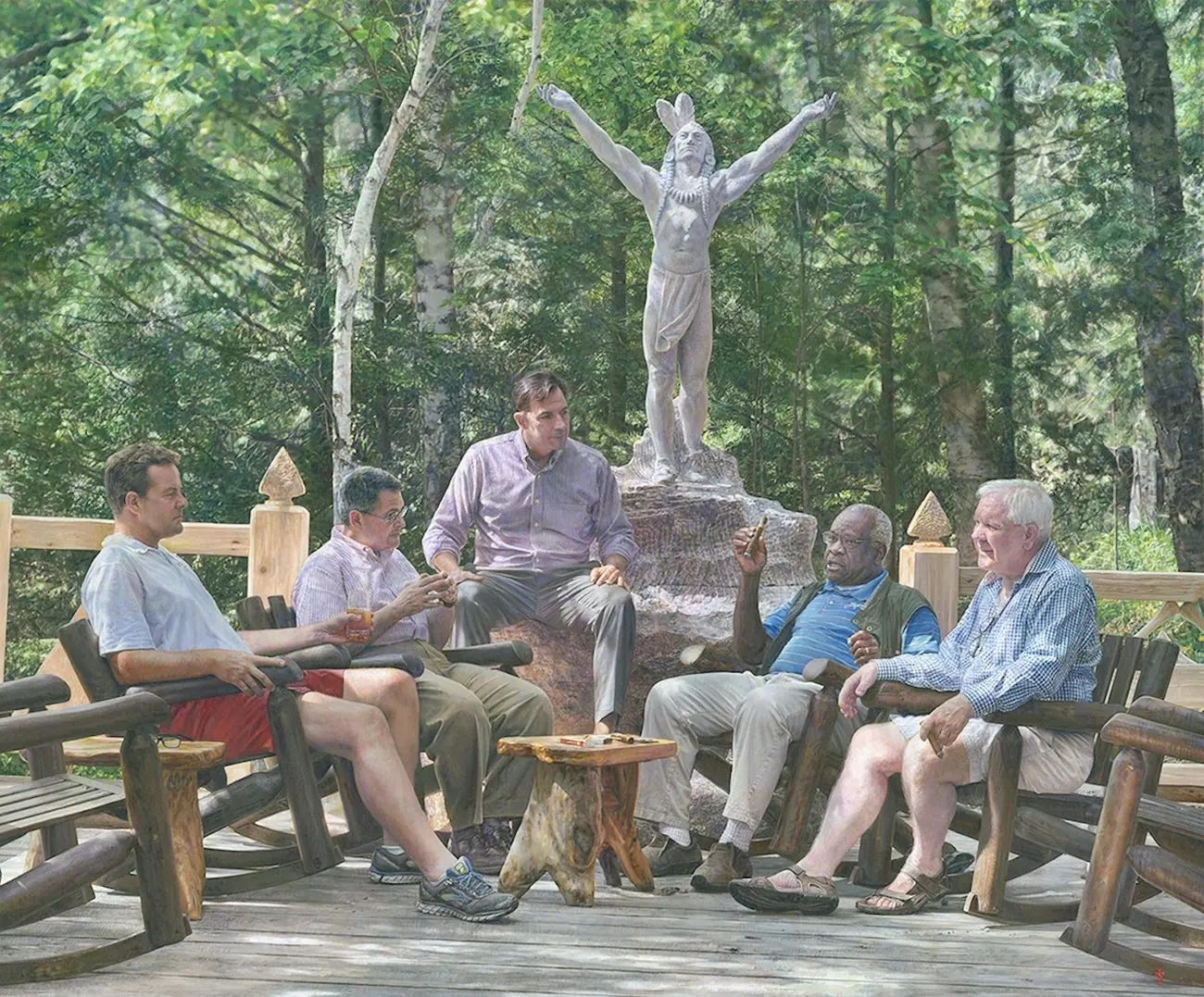

It is a strange painting. No one looks as dignified as you might expect them to. All this wealth and influence between them, and they look like leaders of a Boy Scout troop or retirees on a fly fishing trip, with ugly footwear to match. Crow looks droopy and uncomfortable, like he forgot to bring his sunglasses. Thomas looks dour, as always.

The cynosure of this painting, which hangs at Crow’s Camp Topridge in the Adirondacks, is not Thomas but a statue of a Native American man. He presides over the semicircle, extending his arms as if to bless their meeting. It is a false and anachronistic benevolence that would be even more shocking were it not without centuries of precedent. The statue functions as a Cigar-store Indian for this smoking circle of the rich and powerful, and thereby whatever rightwing ideologies are discussed here: originalism, Paleoconservatism, American nationalism. The function of this statue is not to mark or commemorate history, nor is it to honor or acknowledge the people who once lived there. It is a willful repositioning of the past so that it might authorize—however untruthfully—the present.

The painting, called “The Conversation,” was featured in ProPublica’s recent report about Thomas’s corruption, years of undisclosed gifts and vacations that Crow showered on Thomas and his family. The scale of corruption was shocking, though what stood out most was Crow’s eccentricity. His private retreat, for instance, has “a lifesize replica of the Harry Potter character Hagrid’s hut, bronze statues of gnomes and a 1950s-style soda fountain where Crow’s staff fixes milkshakes.” He also owns a vast collection of historical memorabilia, including a statue garden full of 20th century statesmen. Churchill, Thatcher, and Reagan stand on an “uphill zone for the good guys,” looking down on the likes of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao in the “downhill zone.” Crow’s rationale for keeping his heroes and villains alike is that “If these statues can be utilized as a tool to remind newer generations of the failure of the bad guys and the triumph of the good guys, then it’s a lesson worth having.”

Good guys and bad guys, that childhood view of History. As the New York Times reported 20 years ago, Crow was inspired to collect these statues by seeing one of Cecil Rhodes, the arch-imperialist, fall in 1979, when Rhodesia was becoming Zimbabwe. “It's an image that has persisted with me for many years,” Crow remarked, “I thought something was being lost from history if a statue of that time was not salvaged.” One need not wonder which zone of his garden Crow would have put Rhodes in had he gotten his hands on that statue.

The many other historical objects displayed in Crow’s estates are also from good guys and bad guys alike. One gift from Crow that Thomas did disclose was a $19,000 Bible that belonged to Frederick Douglass. Crow owns Napoleon’s desk and Wellington’s sword. He has a death mask of Sitting Bull. Most controversial are several Nazi artifacts: at least one painting by Adolf Hitler (which apparently hangs next to one by Norman Rockwell and one by George W. Bush), Hitler’s teapot, and linens stamped with swastikas. Visitors to his estate have reported being shocked at the lack of context.

The thought that Crow might add context to his collection misunderstands the whole point of this kind of History, which is an adolescent and idolatrous sort. Crow’s is the version of History that Jacques Rancière defined as “an anthology of what is worthy of being memorialized. Not necessarily what was, and what witnesses testify to, but what deserves to be focused on, meditated upon, imitated, because of its greatness. […] No matter what has been claimed, it is not events that lie at the heart of this kind of history, but examples.” History here is not something you study but a series of self-evident instances of greatness, by good and bad guys. It is the History of Trump’s ill-fated National Garden of American Heroes, of the 1776 Report. It is dangerous less because it will turn you into a Nazi (no promises, though) than because it is so incomplete, so untruthfully small.

For men like Crow, there are only so many worthy examples, only so many Great Men and Great Books. Thinking that historical memorabilia could constitute History is to reduce the latter to a small stack of baseball cards that one can bid on, buy up, and deal out on a table. It is the idea that one can understand something not by study but by ownership. And if History is a finite series of examples, one could own them all.

Of course, once you own something, you get to decide what to do with it. Ownership is how Crow asserts his influence. The real estate magnate is one of several architects of the rightward slouch in this country, a leading donor to rightwing causes. He is involved with countless conservative institutions, having sat on the board of the American Enterprise Institute, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, and the Supreme Court Historical Society, to name a few. Nearly every conservative politician and pundit you can think of has been to his mansions, seeking favor or campaign funds, amid his odd array of contextless objects.

It follows that Crow’s friendship with Thomas has produced its own historical objects. The ProPublica report mentions a $105,000 donation Crow made to Yale Law School, Thomas’s alma mater, as a “Justice Thomas Portrait Fund.” He also commissioned a bronze statue of Thomas’s eighth grade teacher, a nun standing over two black children. As a friend and benefactor, Crow is invested in Thomas’s legacy. But, like the men who buy up first editions of books they will never read, perhaps he hopes, too, that some of the grandeur will rub off on him, that their legacies will continue to intertwine. The reason for “The Conversation” may have been to celebrate that day or to have something to hang on the wall, but it also places Crow himself next to Thomas. In History. Another painting Crow commissioned has him grinning goofily on a boat next to another friend: George W. Bush.

The people for whom History is the weight of Hitler’s teakettle in their hands are not after understanding or truth. They are after ownership, power, and the preservation of a certain type of legacy: one that you can buy. Lenin and Thatcher sharing the same statue garden is not as dissonant as it might seem, not merely because they are positioned in a chess-match of good guys and bad. The sheer fact of each statue undergirds Crow’s desire that history be a small collection of notable figures. It’s easier to manipulate that way, easier to own. Good guys and bad guys—it matters little whose faces are on the caryatids that hold up such a man’s delusions.

ben tapeworm